There are two primary underlying Japanese cultural traditions relevant to their aesthetics. The first is deeply rooted in the Zen philosophy that reality is essentially impermanent, absentany belief of a spiritual realm behind it. The arts in Japan consistently reflect this fundamental impermanence—sometimes mourning, sometimes rejoicing in it. The second observation is that the arts in Japan are associated with Confucian practices of self-cultivation, more closely connected with intellect and the life of the mind than in the western traditions. Since the introduction of Confucianism in the 3rd century, and Zen Buddhism in the 8th century AD, Japan’s evolving aesthetic traditions consistently reflected these two significant influences to eventually become the modern formal Japanese Aesthetic.

Mono No Aware, literally “the pathos of things”, and also translated as “a sensitivity to ephemera”, is a Japanese term for the awareness of impermanence. The term is meant to focus awareness on the impermanence of all beauty. Included in that awareness is the bitter-sweet experience of a quiet sadness at the inevitable passing of all things, and also a heightened appreciation of the inherent beauty of each. The term, which underscores the of the passage of time and the choice to embrace rather than rally against the inevitable, is illustrative of a quiet Japanese cultural strength born of ancient wisdom.

Wabi aesthetics emphasize simple, austere, or understated beauty as a vehicle for recognizing the basic condition of impermanence. In the Zen tradition, to value only certain epitomic moments of the eternal flux may indicate a neglect to accept that basic condition. The Wabi aesthetic quality of simple, austere beauty conducts a deliberate effort to perceive the authentic existential beauty of each and every moment. By purposely assigning value to understatement and imperfection, no object or the moment in which it exists, goes unappreciated.

Sabi originally signified, “to become desolate”, as all which exists must, given the persistent Japanese viewpoint that life is understood best as impermanent in character. Later on the term seems to acquire the meaning of something that has aged well, grown rusty, or has acquired a patina that makes it beautiful. This quote by the late Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, one of the major writers of modern Japanese literature, illustrates the essence of the Sabi aesthetic, “We do not dislike everything that shines, but we do prefer a pensive lustre to a shallow brilliance.. . . a murky light that, whether in a stone or an artifact, bespeaks a sheen of antiquity. . . . We love things that bear the marks of grime, soot, and weather, and we love the colors and the sheen that call to mind the past that made them.”

Yūgen, or grace, is the Japanese aesthetic which invites us to venture outside the confines of our habitual perceptions of reality. The term yūgen appeared first in Chinese philosophical texts, where it has the meaning of “dark,” or “mysterious.” Mysteriousness in one form or another, is thematic of all Japanese aesthetics which favor allusiveness over explicitness and imperfection over completeness, but the Yūgen aesthetic takes the mystery to a whole new level. The Japanese author Kamo no Chōmei wrote the following as characterization of:

“When looking at autumn mountains through mist, the view may be indistinct yet have great depth. Although few autumn leaves may be visible through the mist, the view is alluring. The limitless vista created in the imagination far surpasses anything one can see more clearly.” The Yūgen aesthetic is an open invitation to use our imagination to unveil mastery everywhere, in perfection and non-perfection alike.

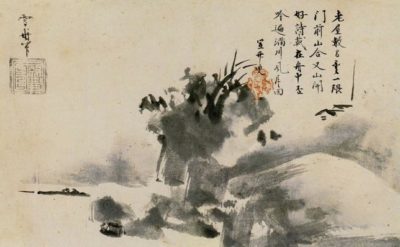

Yūgen and Landscape Painting is among the Japanese aesthetic practices referred to as geidō. Geidō 芸道 literally means “the way of art” and refers to the mental practice of emphasizing the techniques and philosophies behind traditional Japanese art disciplines, in effect appreciating and honoring the process of creation itself and expanding the Yūgen aesthetic to express both the philosophic and religious.

Sesshū Tōyō was a seminal Japanese artist whose landscapes, particularly the “Splashed Ink Landscape, epitomize the yūgen aesthetic. The “splashed ink” technique Sesshū employed, was one of several spontaneous “broken ink” techniques including washes and splashes, ink-flinging, and dripping. The most demanding style, “splashed ink” was considered the highest form of expression and required mastery of bodily movements that created the work. The invitation to focus on the process of creation, and the images produced not fully formed, disrupts the habitual “story-telling” of the human ego, and a glimpse of our oneness with the continuous motions of nature gleams through the rift.

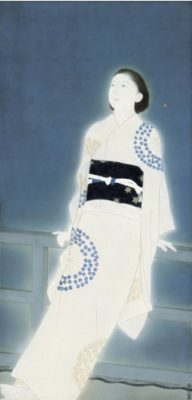

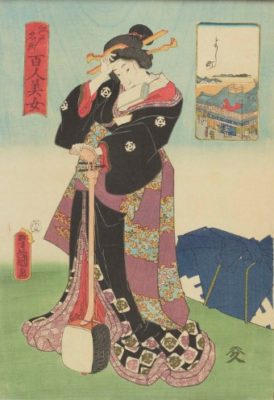

Iki which roughly translated means, “chic”, or “stylish, is a relatively new concept in Japanese aesthetics. In the 17th century, the word “iki” began to be used to describe the ultra-refined dress and manner of Geisha during the Meireki Era. Iki shares concepts such as austerity, and existential beauty with the other Japanese aesthetics of Wabi and Sabi and a foundation which emphasizes both style and subject matter with the Yūgen techniques. . . it is unabashed, and completely lacking in detrimental self-consciousness. As a style, not generally tied to a specific form, Iki can be at once simple and sophisticated, ephemeral or straightforward, measured or audacious, smart or romantic – a study in contradictions.

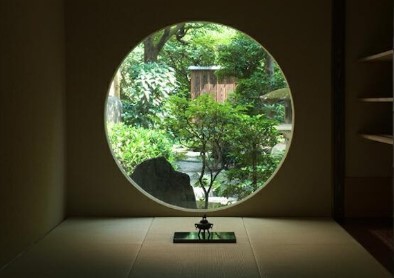

Kire, meaning the “cut” or “cut-continuity”, is distinctively featured in the Japanese artistic disciplines of ikebana, Nō theater, haiku poetry and garden-art. In the Japanese art of flower arrangement called ikebana, literally “making flowers live”, the Kire aesthetic “cut” separates the flower from its roots in order to let the true nature of the flower be revealed.The “cut-continuation” aspect of Kire is expressed in the performance of the highly stylized gait of the consummate actors of the Nō drama. Similarly, in the art of haiku poetry, the “cut-syllable” (kireji), cuts off one image from the following while at the same time linking it to the next. Finally, The Karesansui, or “dry landscape” rock gardens are characterized by a miniature stylized landscape “cut off” from the rest of the world. Consistent to each of the Japanese aesthetics and to their culture, Kire acts as artistic agent to convey the collective embrace of Zen principles, with special emphasis on the impermanence of all forms, and “less is more”.

Below is an apt expression from the Buddhist priest, Yoshida Kenkō, of the Kire aesthetic:

It does not matter how young or strong you may be, the hour of death comes sooner than you expect. It is an extraordinary miracle that you should have escaped to this day; do you suppose you have even the briefest respite in which to relax? (Keene, 120)

In the Japanese Buddhist tradition, awareness of the fundamental condition of existence is no cause for despair, but rather a call to vital activity in the present moment and to celebrate and express gratitude for each moment granted to us in the eternal flux of the authentic nature of reality.

Come Visit Art De Tama Fine Art!

Japanese artist in the United States. Tamao Nakayama was born and raised in Tokyo, Japan, and moved to the U.S. when she was 25 years old. She is still deeply influenced by the Japanese aesthetic, and the belief that ‘less is more’. She is a minimalist abstract artist. She paints and sculpts.